Kathleen Singh MD, Beverley Cassidy MD

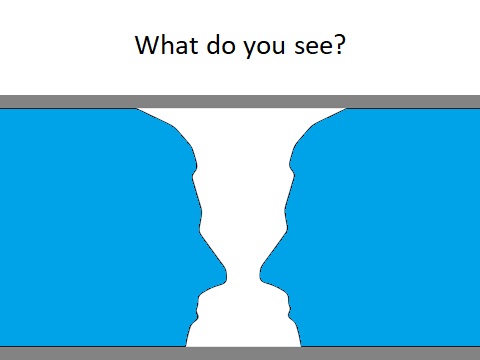

The iceberg principle: it is the tendency of the human mind to perceive only a small piece (the "tip" of an iceberg's mass) of reality through a limited lens (see Figure 1). The lens can shift, and perspective can change!

Using the iceberg principle to our advantage will enable us to: (i) recognize that our viewpoint is a limited cognitive lens at any given moment, (ii) imagine and be aware of other perspectives, and (iii) develop cognitive flexibility.Cognitive flexibility (or permitting our lens to shift) is a great life skill and is associated with many other adaptive qualities found in resilient thinking. Cognitive flexibility is related to a sense of wellbeing.

Figure 1. The iceberg principle

From a historical perspective, Aristotle used the term “eudaimonia” in his work for highest human good. Eudaimonia is derived from Greek, where “eu” means good and “daemon” means spirit. It translates into having a good, indwelling spirit or ”human flourishing”.

Aristotle believed that happiness was related to good living, such as taking perspective on what aspects of our lives are meaningful and give us a sense of purpose (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. From The School of Athens, Raphael's 1509 fresco, showing Aristotle (right) and Plato (left)

Positive cognitive set is correlated with other key protective factors such as higher reported happiness, secure attachment relationships, and problem-solving skills (Kobau et al, 2011).

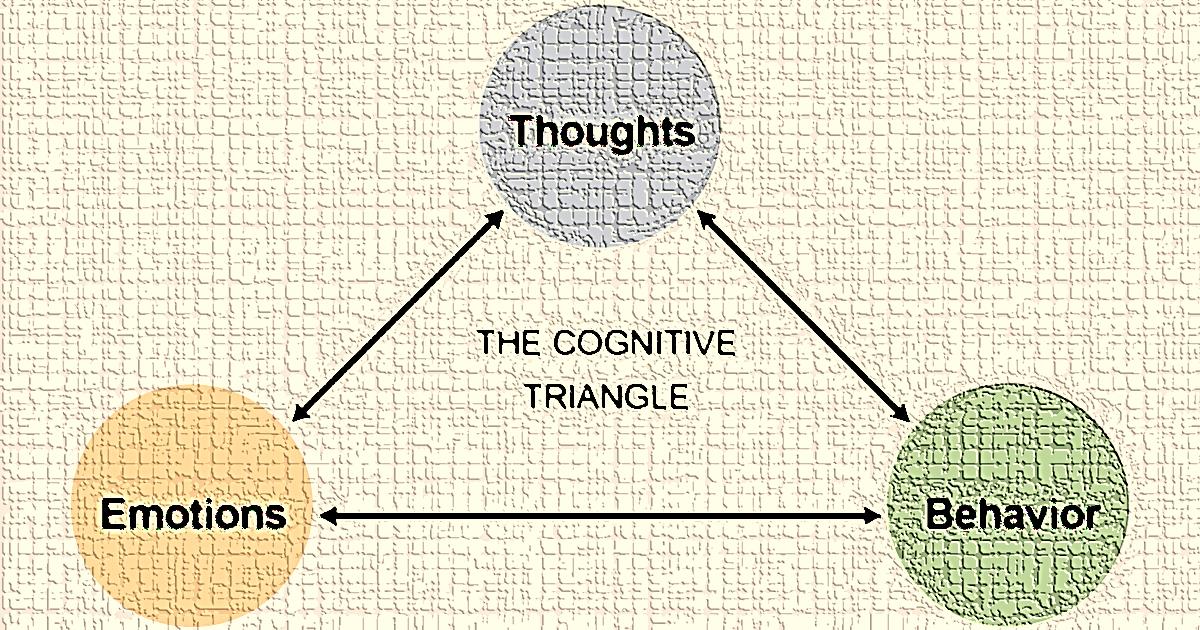

The cognitive triangle: first proposed by Aaron Beck in 1976, it depicts how thoughts, emotions, and behaviours all influence each other (see Figure 3) (Beck, 1976; Burns, 1980; Burns, 1989).

Figure 3. The cognitive triangle (Beck, 1976; Burns, 1980; Burns, 1989)

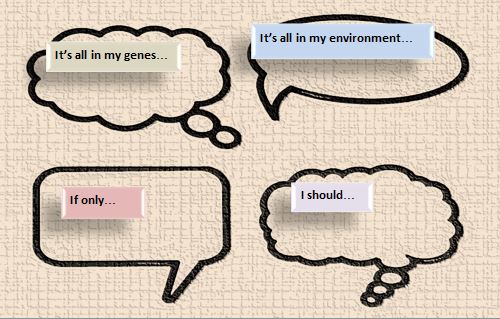

Misappraisals impact our wellbeing (see Figure 4 for common misappraisals). A misappraisal is the failing to perceive or value the things that have evidence to promote our wellbeing, focusing instead on things that have little evidence to support their role in improving a sense of wellbeing.

To learn more about the common misappraisals illustrated in Figure 4, click on the thinking traps below.

Figure 4. Common misappraisals

Trap #1: It’s all in my genes...

What percentage of perceived emotional wellbeing (happiness) is genetically determined by inherited family genes? What determines happiness?

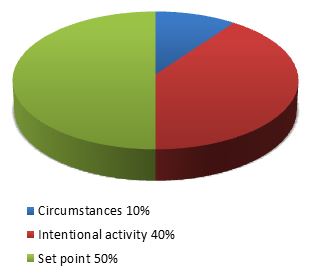

Figure 5. Determinants of happiness (Data derived from Lyubomirsky et al, 2005)

Trap #2: It’s all in my environment...

Which event would produce a profound and long lasting impact on our overall happiness level?We all dream of winning the lottery, but it will not buy us lifelong happiness. Researchers in Illinois in the 1970s interviewed lottery winners who won between $50,000 and $1,000,000 (remember, this is the 1970s) and found that only one year after winning, their happiness levels were no different than the group who did not win. In fact, the lottery winners noticed that they experienced less enjoyment from ordinary day to day activities compared to the non-winners. This difference was statistically significant (Brickman et al, 1978).

Marrying your soul mate is a good idea but it will not have long lasting effect on your happiness level. Although there were individual differences, on average, people experienced a happiness boost for two years after marriage, followed by return toward baseline levels (Lucas et al, 2003).

Although we may assume that severe medical illness will leave to unhappiness, the effect is not long lasting. It appears that hemodialysis patients adapt to their medical illness and new health status. Although they report their own health to be worse than others, this does not appear to have a significant impact on overall happiness (Riis et al, 2005).

Although accident victims did find everyday events less enjoyable than controls, this was not statistically significant. Ratings of past happiness and present happiness were significantly lower than controls, but there was no difference in ratings of future happiness (Brickman et al, 1978).

Positive psychology research shows that personal attitudes and behaviours can be more impactful for long-term sense of wellbeing than extremely positive/negative life events.

Traps #3 and #4: The “I should...” or “If only...”

Do any of these statements sound familiar to you?The good news is that 40% of our happiness level is dictated by intentional activity, and hence, it is under our control.

The bad news is that, in general, we do not have an accurate view of what increases happiness levels, and often what we think will make us happier in fact can do the opposite, or have no impact on overall happiness level.

It is about hedonic adaptation! Hedonic adaptation is the observed tendency of humans to quickly return to a relatively stable level of happiness despite major positive or negative events or life changes. Or, in other words, no matter if we win the lottery or get a divorce, we go back to our usual level of happiness eventually (Brickman et al, 1978).

The effect of hedonic adaptation is a form of emotional and cognitive habituation to positive or negative stimuli. Research shows that it seems to be stronger when related to changes in life circumstances, and a weaker effect is observed in the case of changes in activity. We habituate less easily to experiences than circumstances.

For this, ensure your activity is:

So, if winning the lottery, finding love, and earning more money do not ultimately change our happiness level over the long term, then what does? Current data on wellbeing and power of resilient thinking has been well captured in The How of Happiness by Sonja Lyubomirsky (2008).

Evidence-based positive psychology skills to increase wellbeing comprise the following:

Dunn et al (2013) found that people who spent money on others instead of themselves were happier. Acts of kindness through money were found to increase happiness most when they involved feeling more socially connected and being able to see the impact of your act directly. This held true across different cultures and socioeconomic statuses.

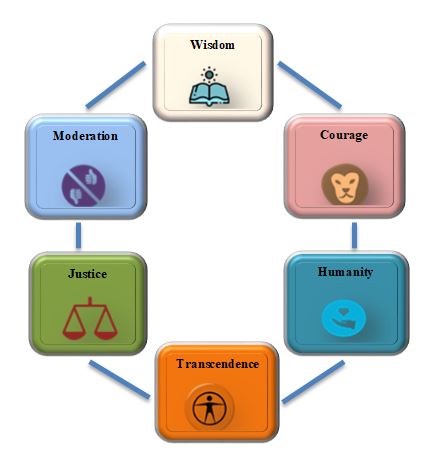

It is important to know our own character strengths and cultivating them in daily life. Figure 6 shows key character strengths as depicted by Martin Seligman (Park et al, 2004; Lyubomirsky, 2008). Visit authentichappiness.com to learn more.

Take a quiz: Character Strengths Survey. The Values In Action Character Strengths Inventory (VIA) survey is a free, online, scientifically validated survey of character strengths. The survey is a 240-question inventory, through which activation of your key strengths is linked to long-term wellbeing. Once identified, use your top strengths regularly by practicing them in daily life. This has been shown to increase your baseline wellbeing significantly (Park et al, 2004; Lyubomirsky, 2008).

Figure 6. Seligman’s signature character strengths (Data derived from Park et al, 2004; Lyubomirsky, 2008)

This is a regular acknowledgement of what is going well in life and knowing what you are grateful for. Gratitude practice is correlated with an increased sense of wellbeing. Visualizing past positive events and anticipating future ones can increase your happiness baseline.

Grateful

This is about reframing situations in a more positive light, and pausing to count one’s blessings.

Example: “I’m so overloaded with work...” Reframing: “I am one of very few given this training. Whenever possible, I want to appreciate the opportunity to learn as much as I can...”Stay focused on important personal goals that are meaningful to you, even when there are many external demands on your agenda. Focus on the journey, rather than the end point. Brunstein (1993) found that the process of working toward a goal or participating in a valued, challenging activity is as important to wellbeing as its attainment.

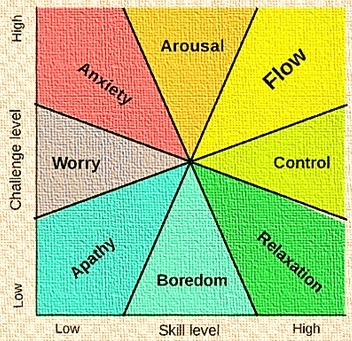

This means a mental state of complete absorption.

”... the best moments of our lives are not the passive, relaxing times... the best moments usually occur if a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997).

“The metaphor of flow is one that many people have used to describe the sense of effortless action they feel in moments that stand out as the best in their lives. Athletes refer to it as "being in the zone," religious mystics as being in "ecstasy," artists and musicians as "aesthetic rapture.” It is the full involvement of flow, rather than happiness, that makes for excellence in life. We can be happy experiencing the passive pleasure of a rested body, warm sunshine, or the contentment of a serene relationship, but this kind of happiness is dependent on favorable external circumstances. The happiness that follows flow is of our own making, and it leads to increasing complexity and growth in consciousness.” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997)

Figure 7. The Csikszentmihalyi’s flow model of the mental state based on challenge level and skill level (Data from Flow (psychology), Wikipedia/the free encyclopedia)

One of Canada's great artists, Maud Lewis, was introduced to the world in a 1965 CBC series portraying the artist at work in and around her house (to view the video, go to the CBC Archives). Maud Lewis and folk art truly captures the spririt of wabi sabi Nova Scotia style. She creatively prospered throughout her life, in spite of considerable adversity - look at her hands in the video (she had severe form of juvenile rheumatoid arthitis) and the size of her paintings, which reflected the fact that she only had a very limited range of motion of her arms... and in spite of this... limitation and imperfection, her art expresses a joy and optimism about the world around her, in spite of the very clear long-term imperfections and hardships she dealt with in her life.

Benefits of mindfulness practice include the following:

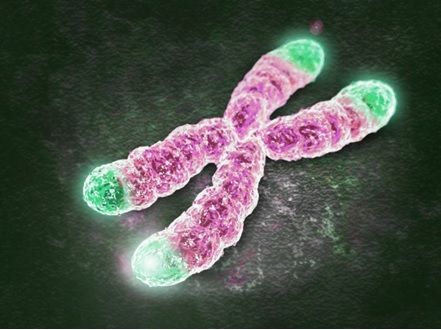

States of focused attention also support chromosomal health. In the interest of learning new things, the chromosomal level is an interesting new place to talk about with respect to mind, mood, and health across our lifespan. Telomeres are DNA-protein structures found at the ends of chromosomes and they play a vital role in protecting the genetic material in our genome. When we are very young, these telomeres are 8,000-10,000 base pairs long (Blackburn et al, 2016).

So what do telomeres have to do with healthy aging? Telomeres act like plastic ends of shoelaces protecting the lace itself from unravelling. Telomeres do the same thing for chromosomes: they keep the active portions of the chromosome protected, and keep them from unravelling or abnormally crosslinking.

Telomere shortening is associated with aging and diseases of aging, including:

Behavioural activity: regular exercise was found to boost mood and vitality lasting up to six months afterwards.

Physical activity and mood regulation: in a Cochrane review of 38 randomized double blind studies (n = 2,326 subjects), exercise has shown significant benefit for mood regulation, including for mild and moderate depressive symptoms.

Physical activity is the number one recommendation for treatment of mild and moderate severity of depression, according to the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines.

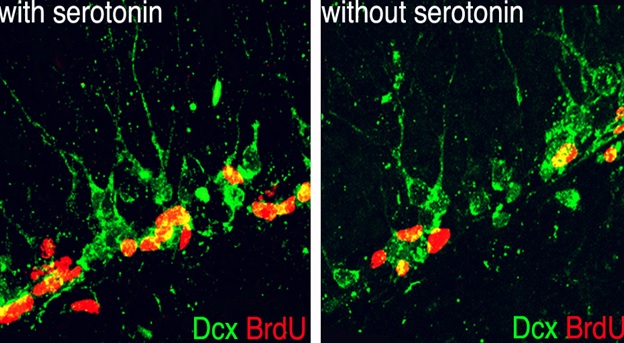

Neuronal firing with running: physical activity is known to be an excellent mood enhancer and even an effective treatment for clinical depression, because exercise activates neurochemistry.

In a meta-analysis of 193,166 subjects, sedentary behaviour has been correlated with a 25% increased risk of depression (Zhai et al, 2015). Staying active is probably the single most effective do-no-harm option for improving your mood, aside from ensuring you are not overconsuming an actual CNS depressant such as alcohol.