Marc Legault MD

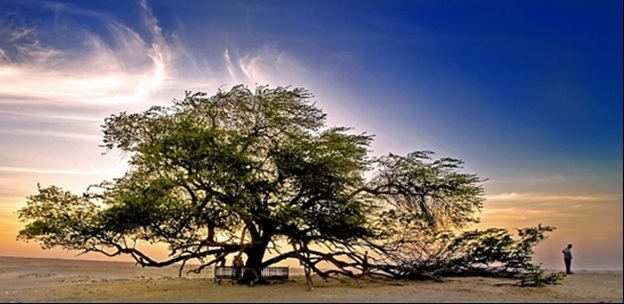

In the desert sand in Bahrain there lives a tree that has withstood the test of time for over four centuries. It has survived in spite of the arid environment, and overcome the challenges brought on by nature and mankind. Its resiliency in the face of these threats is drawn from a variety of innate strengths as well as support from the community whose members revere its presence, and have implemented fencing and other structural supports to protect it from the latter. Its legendary status and spiritual significance for the community supports its continued growth through protection against vandalism and man made threats. It has gained public attention, attracting tourists from all over the world, who are drawn by its fortitude and magnificence.

Image credit: Faisal Ansari; used with permission

The example laid out previously is an illustration of resiliency, but also highlights the idea that resiliency is a conceptual framework that can be applied not only to wellbeing. In fact, the term resiliency was initially defined in the field of metallurgy, referring to a metal’s capacity to withstand force without disrupting its physical integrity. The Canadian Oxford dictionary defines resilient as: 1) (of a substance etc.) recoiling; springing back; resuming its original shape after bending, stretching, compression, etc, and 2) (of a person) readily recovering from shock, depression, etc.

With that having been said, even with the increased interest in understanding of resilience as a desirable quality, no universal definition exists in the health literature. Aburn et al (2016), in their systematic review containing 100 articles, also added that definitions of “resilience” that do exist span across 15 different themes, which they then collapsed into five categories. We will not cover all of those here; however, we will further look at three different conceptualizations of the term that have elsewhere appeared in the literature.

Historically, the view of resilience has been that it is an inborn trait, one that has allowed individuals in traumatic circumstances to withstand, and even flourish, in spite of these. Consider the comparison of the dandelion and the orchid, initially conceived in the context of children in possession of one gene (trait) who appeared more capable to buffer the effects of early childhood trauma, relative to children of a different phenotype. The dandelion is capable of surviving in a variety of different settings; it has the capacity to be resilient because of inherent traits that allow it to do so. The orchid, on the other hand, can only bloom under certain conditions of temperature, rainfall, soil nutrients and pH, sunlight, etc (Boyce & Ellis, 2005).

Winkel et al (2018) suggest that factors contributing to resilience can be divided into internal (personality traits like optimism and altruism) and external factors (see below). In addition, the internal factors may represent innate traits or qualities, although they may also be things that can be trained and enhanced, which leads us to our second conceptualization.

Thinking about resiliency in this manner shifts the influence a person has over their ability to exhibit resilience. By definition, individuals have some inner potential to boost or train their resiliency “muscles.” They might choose to enhance certain skills (through balancing out automatic negative or distorted thoughts, mindfulness, meditation, or reflection) or boost their ability to be resilient by addressing external factors like accessing social supports, sleeping and eating properly, controlling one’s schedule or extracurricular activities taken on. Thus, there are things, including a person’s innate traits (see section (a)), which can serve to increase the capacity for resilience. Likewise, there are certain negative activities and environmental exposures that can reduce a person’s capacity for resilience. See the “Did you know?” section below for more information.

There is a variety of models for how to describe resilience that are about as diverse and creative as can be. One is the idea proposed by Dunn et al (2008), where they define resiliency versus burnout using the model of a “coping reservoir” with a “tank” whose dimensions are determined by inherent traits, and whose inputs (positive and negative) either fill or drain the “tank.”

Perhaps the most encompassing of the conceptualizations of resiliency, and the one most fitting in terms of medical training, is that of a process to be undertaken. Stripped to its bare essentials, this process looks like the summation of adversity and positive adaptation (Luthar et al, 2000).

Defining adversity can be difficult. While previously defined as “any hardship or suffering linked to difficulty, misfortune or trauma” (Jackson et al, 2007), other researchers have adopted a more broad definition, as discussed below. Indeed, adversity can arise in a particularly challenging situation, but this may not necessarily be an objectively “negative” situation (Fletcher & Sarkar, 2013). (For more information on personal adversity and coping style(s), see the section Know Yourself, topics 4 and 5.)

For example, consider in Canada the calendar day of July 1st from a residency perspective: this is the date where individuals will “graduate” from one postgraduate year to the next, a progression that is demarcated only by the clock striking midnight. It is even the arbitrarily chosen day when one goes from a medical graduate to begin practice as a licensed physician for the next year, until their licensing body requires a contract renewal the following summer. This annual renewal comes with a salary raise, a change in clinical rotation, and, perhaps most importantly, a change in expectations.

In the five-year residency programs in Canada, the second to third year transition is one of junior to senior, and increases responsibilities, particularly on call. For example, in Ontario, psychiatry residents, upon completion of their child and adolescent psychiatry rotation, are capable of moonlighting; in a sense, acting like a consulting staff in community emergency room settings. While these are not negative per se, they do provide new and unique challenges, demands, and stressors previously not encountered.

Winkel et al (2018) provide another conceptualization, this time looking at resiliency in residency, using a tree as the person’s professional development. Their model is dynamic and process oriented, and takes into consideration a person’s professional development that takes into account certain intrinsic values and guiding principles, which serve to direct this growth. The growth is strengthened, else hampered, depending on how each new challenge is received and highlights the importance of positive affect, self-esteem, and self-efficacy.

Recalling the tree-of-life story, which of the following examples represent its resilience?

Another term worth operationalizing is that of “wellness”. It has been defined as an orienting concept that represents one pole of a spectrum whose opposite pole is one of pathology. It is, however, more than simply the absence of pathology. It comprises the accumulation of positive behavioural (exercise, adequate nutrition and sleep) and psychological (satisfaction with oneself, a sense of control over one’s fate, a sense of purpose and meaning) elements. The content and importance of these elements is value laden and depends on a person’s age, race, culture, religion, creed, gender identity, and other socioeconomic factors. There is no universal example of wellness (Cowen, 1991).

Curricular culture can have an impact on an individual’s resilience, including supportive and clear guidelines around absenteeism, and clear support of mental health issues (Watling, 2015) and direction of how to obtain available resources (see section Integrate New Lifestyles). It has been suggested that transformative education or other resiliency enhancement strategies might improve a person’s capacity to become resilient (Sanderson & Brewer, 2017).

Here we provide a few examples of proactive program measures to reduce that “baptism by fire” or “sink or swim” mentality classic to medical training. These might include:

Evident is the fact that the face of adversity in training is constantly shifting with the intent of programs to deliver enough opportunity for the learner to constantly be in a state of challenge that ignites an inner drive to push learners a little further. One does need to take the time to appreciate the moments of even small accomplishment to avoid becoming callous to the ever-changing playing field. It is ingrained in medical training that as soon as one becomes comfortable on a rotation (e.g., knowing where the appropriate forms are, how the unit is run, know support staff by first name) they are switched to another rotation, only to start over again. This “carousel ” like feeling of always being in motion but seemingly always returning to the same kind of beginning is really more like a spiral staircase, where the surroundings look similar, but from a slightly “higher” vantage point.

Just as medicine is a career dedicated to life long learning, so does the process of resiliency to transcend length of time in practice. Adversity does not of course end with completion of training, although each step presents new challenges and opportunities, and depending on a person’s experiences, the same stressors might lead to very different outcomes. Looking at transition to practice, some common challenges include billing/reimbursement errors, delay for licensing, negotiating a fair contract, establishing a lasting network of supportive colleagues, how to balance family and work, moving, examination fees and starting to pay off loans. The days of placating lip service statements such as “It’ll all work out,” or “Don’t worry, you’ve come this far,” which serve little other than to provide some vacant reassurances that momentarily stave off anxiety, are gone. It is incumbent on training programs to help facilitate sessions directed to senior residents to provide pragmatic support, and ideally, to pull individuals from a diverse range of working environments (community, rural, non-academic positions) to provide a more comprehensive picture of what is actually available outside academic centres.

Fox et al (2018) performed a systematic review of interventions used to foster resiliency and identified ten unique interventions with low to moderate effect sizes. (For more on interventions, see the section Integrate New Lifestyles.)

An emergency medicine resident is returning to work after 10 months of medical leave. During that time, she underwent electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for major depressive disorder, which is now in full remission. She is returning on a graduated schedule that will have increasing clinical time weekly as tolerated as she transitions back. This will permit her to scale up or down her workload as she gets herself back into the swing of things. She is going to weekly follow-up appointments with her treating physician and is on a maintenance antidepressant. The rotation she is starting back on is one she was on prior to leaving, which is adult critical care, and where she will likely be exposed to a lot of patients with severe struggles including mood problems and losses. She worries about the impact speaking with these individuals will have on her own recovery, and she decides this would be a good topic to bring up with her own physician at their next appointment. She has prepared with her physician how she will respond if she is asked why she was off by her supervisor or any other co-residents. She is planning to continue with her daily bike rides, which she started during her time off.

Check off below all the statements that demonstrate her resilience.

Each medical specialty has its own version of specific challenges. For example, the following list as shown in Table 1 is by no means exhaustive, but offers a glimpse into the specific challenges present in the specialty of psychiatry.

| Table 1. Challenges faced by residents in psychiatry |

|---|

| Attempted and completed suicide of patient |

| Chronic, relapsing nature of some illnesses in patients |

| Third hand exposure to traumatic histories in some patients (see sect. Know Yourself, topic 8) |

| Perception of being seen as “outsiders” within medicine |

| Assessment of decisional capacity and involuntary status of patients |

| Often operating in “grey” areas of ethical management of diagnostic uncertainty |

| Patient-physician boundary setting |

| Lengthy training with extended periods of exposure to subspecialty areas |

| Keeping current with all recent advances in pharmacological and other somatic treatments |

| Patient’s readiness and willingness for change is not always congruent with physician’s readiness to treat |

| First year off service rotations (applicable to Canadian and U.S. training) on other medical specialties |

Which of the following is true?