Olga Yashchuk MD, Terry Chisholm MD, Cheryl Murphy MD, MEd

The balance between a meaningful and rewarding medical practice versus a demanding and stressful one can be the difference between an engaged physician and a physician who is suffering burnout. First, we will take a look at what makes an engaged physician. What do you think some traits of an engaged physician are?

(Anandarajah et al, 2018)

Unfortunately, as physicians, we are not always engaged. Various stressors on the job can lead to burnout. Although burnout was described in detail in the preceding topic (Recognizing Burnout), we briefly outline here what exactly burnout is and how it happens. We will start with the risks for burnout.

(Maslach & Leiter, 1997; Shanafelt et al, 2016)

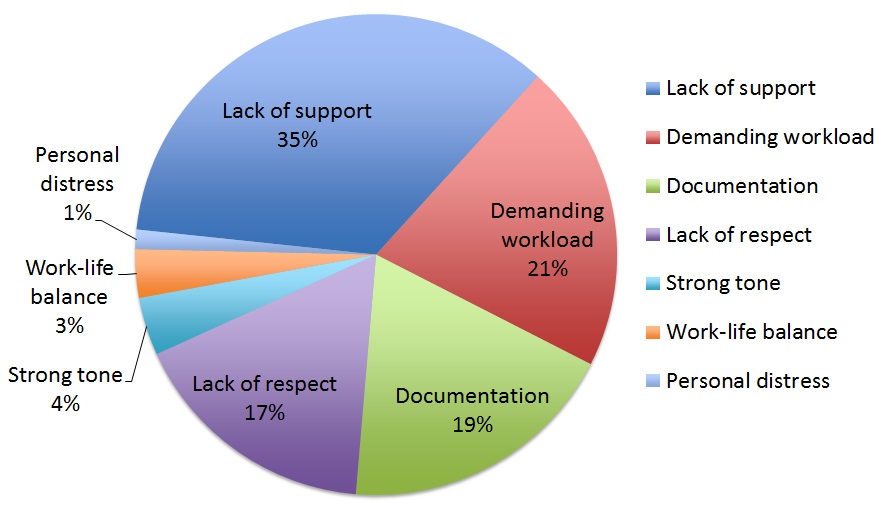

Burnout is a multifactorial, work-related phenomena that involves the interplay between one’s own personality style and coping strategies as well as the demands that are put on each one of us by our environments. Possible environmental contributors are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Environmental contributors to burnout

A recent study at the University of Rochester sent out a 15-question survey to 528 physicians in internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry (Anandarajah et al, 2018). The response rate to survey was 80%. The authors noted a number of themes that were related to burnout as outlined in Figure 2 (Anandarajah et al, 2018).

Figure 2. Themes associated with increased burnout (Data derived from Anandarajah et al, 2018)

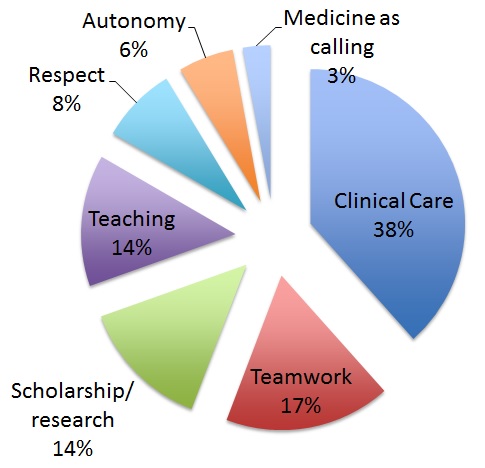

The same study at the University of Rochester was able to show themes related to meaning in professional work, which may help us focus on improving life for physicians (Anandarajah et al, 2018) (see Figure 3).

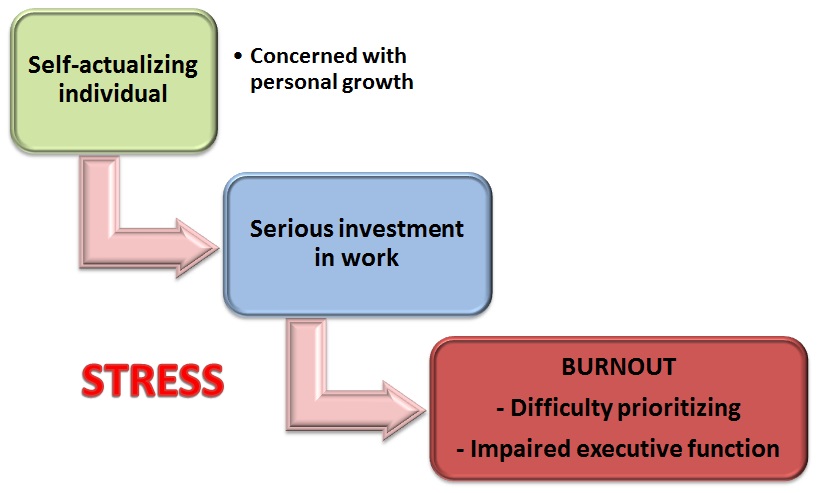

The difference between stress and burnout is the ability to recover and bounce back in the time off from work during stressful situations. Figure 4 shows the sequence from stress to burnout.

Figure 3. Themes reported as sustaining a sense of meaning in professional work (Data derived from Anandarajah et al, 2018)

Figure 4. Path to burnout (Derived from Maslach & Leiter, 1997)

Many psychiatrists work with trauma survivors and this can induce its own particular variation of burnout, which include vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue. There are a number of differences between these two states.

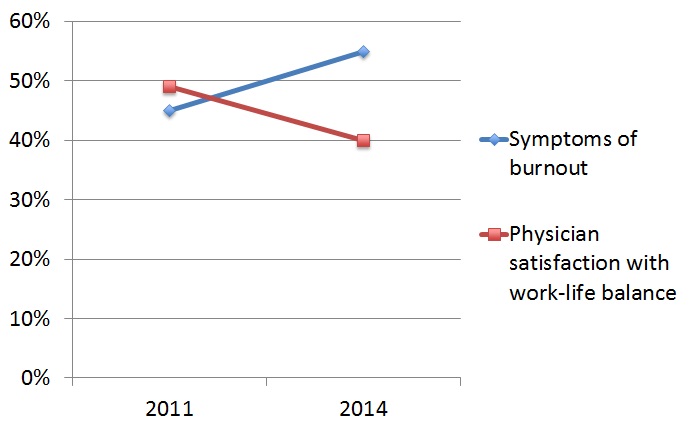

Much variability was found in studies around the world. Burnout is more common in medical students, residents and early career physicians than in the general population (see Table 1) (Anandarajah et al, 2018; Dyrbye, 2014; Ishak et al, 2009; Tijdink et al, 2014). In a recent study by Anandarajah et al (2018), 45.6% of academic physicians at the University of Rochester reported burnout. Burnout is increasing with time as the satisfaction with work decreases (see Figure 5) (Shanafelt et al, 2015). Burnout is rising for all physicians, but especially women. Burnout is reported 1.6 times more often in women (McMurray et al, 2000). It is related to physician's inability to meet both demands of home and work life, as well as a lack of workplace control; moreover, being a mother with young children adds extra stress to women (Tijdink et al, 2014).

| Group | Burnout % |

|---|---|

| Medical students | 28-45 |

| Residents | 27-75 |

| Practicing physicians | 45.6 |

Figure 5. Correlation between work satisfaction and burnout over time (Data derived from Shanafelt et al, 2015)

Which of the following are risk factors for Phillipa to become burned out?

| Table 2. Impact of burnout on physicians (Wallace et al, 2009) |

|---|

| Increased number of workdays missed |

| Less productivity and efficiency in the workplace |

| Interest in early retirement |

| Job turnover |

| Table 3. Specific traits of burnout in physicians (Tijdink et al, 2014) |

|---|

| Physical exhaustion |

| Mental exhaustion |

| Cynical attitude |

| Lack of sense of personal accomplishment |

| Decrease in empathy |

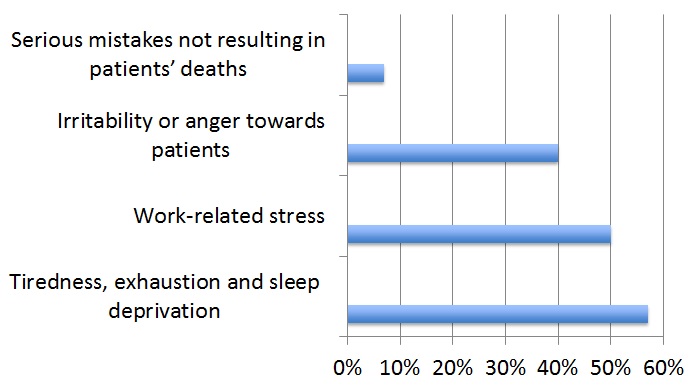

Firth-Cozens and Greenhaligh (1997) looked at the effect of stress on patient care; 225 physicians who participated in the study were from a group of 318 fourth year medical students who were followed up over 10 years and were asked questions on stress, coping, and their attitudes to work and career choice.

Figure 6. Survey of physicians' perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care (Data derived from Firth-Cozens & Greenhaligh, 1997)

Now we will look at a study in resident physicians. Fahrenkopf et al (2008) looked at the rates of medication errors among depressed and burned out residents in a prospective cohort study; 123 residents in three pediatrics residency programs participated. The cohort study showed rates of medication errors in burned out or depressed residents; 74% of participants met criteria for burnout, whereas 20% met criteria for depression. Depressed residents made 6.2 times more medication errors per resident per month compared to residents who were not depressed. Those participants who were depressed or burned out reported poorer health and higher rates of errors compared to those not burned out or depressed. Table 4 shows the rates of medication errors in this study population (Fahrenkopf et al, 2008).

| % of resident group | Medication errors | |

|---|---|---|

| Burnout | 74% | No statistically significant effect found |

| Depression | 20% | 6.2 times more often than non-depressed |

Similarly, surgeons were also found to have more medical errors when they were experiencing burnout. In 2010, Shanafelt and colleagues sent surveys to members of the American College of Surgeons and had 7,905 responders. The survey included self-assessment of major medical errors, validated depression screening tool, and standardized assessment of quality of life.

A survey of University of Ottawa physicians has found that 50% thought about leaving academic medicine every week, and 30% thought of leaving medicine altogether (Wallace et al, 2009).

With higher turnover rates, costs to recruit and retain physicians will also increase. Cost to replace a physician in the U.S. is estimated to be between $150,000 and $300,000 (the estimate includes searching and interviewing candidates and paying for a locum tenens physician, and does not include training medical students and residents, signing bonuses, and moving costs.)