Ana Hategan MD, Caroline Giroux MD

Awareness is the first important step to enhance resilience and wellness, and mitigate burnout. Although stress is inevitable, burnout can be preventable or mitigated. Through this virtual teaching platform, physicians in training can gather information on the resilience and wellness of residents by adopting creative approaches to teaching, in order to achieve awareness and become active partners in preventive care. We hope that this conveys a clear message that we, as healthcare professionals and educators, do not only care for patients but we are required to care for ourselves. A supportive work environment is important to the resilience and wellness of physician trainees in order to help them thrive. Teaching tools to empower physician trainees to foster personal resilience and wellbeing should be an essential part of residency training programs. We aim to define how to characterize resilience and burnout and thus create a targeted curriculum.

Awareness is the first important step to enhance resilience and wellness, and mitigate burnout. Although stress is inevitable, burnout can be preventable or mitigated. Through this virtual teaching platform, physicians in training can gather information on the resilience and wellness of residents by adopting creative approaches to teaching, in order to achieve awareness and become active partners in preventive care. We hope that this conveys a clear message that we, as healthcare professionals and educators, do not only care for patients but we are required to care for ourselves. A supportive work environment is important to the resilience and wellness of physician trainees in order to help them thrive. Teaching tools to empower physician trainees to foster personal resilience and wellbeing should be an essential part of residency training programs. We aim to define how to characterize resilience and burnout and thus create a targeted curriculum.

With our online teaching initiative we endeavour to provide trainees with resources and tools to recognize and actively engage in managing stress and burnout. We aim to engage experienced physician trainees to offer advice on what their peers could do to avoid burnout during training and become a more engaged, satisfied, and resilient physician. In striving to create a useful resource, we plan to build a collaboration of educators who are enthusiastic, inspiring, and who support the physician trainee participants in feeling like they, themselves, make a difference through building capacity and enhancing the system to take care of our own.

We face a sustainability challenge in our medical education. Thus, focusing on medical school curriculum on physician resilience in today’s technologically and socially complex and high resource consumptive world is our primary focus. We acknowledge the paradoxical tasks of training competitive and well equipped residents and fellows to practice medicine in this highly intense resource consumptive world while simultaneously building a bridge to a world all but guaranteed to telescope these levels of complexity and consumption with its all inherent stressors based upon the interplay between economic and ecological forces.

It is possible that the change in medical culture may eventually come from medical schools as well, with leading the way by practicing physicians in the field. However, given the serious nature of the problem, a current passive approach to sustainability of medicine is unacceptable and medical schools must acknowledge the problem and begin to act.

Finally, medical educators are increasingly choosing or being required to shift to online teaching (Maggio et al, 2018). We herein provide a conceptual framework for creating an initiative for physicians in training to better understand and improve their experience of wellness, resilience, and burnout during training while transitioning to online teaching.

Some believe that Maslow’s fifth basic need for self-actualization may be our highest calling (Maslow, 1943), whereas others posit that Viktor Frankl’s creation of a “life of meaning” should be our utmost desire (Frankl, 2006). We know that self-actualizing individuals are self-aware and concerned with personal growth and fulfilling their potential. Thus, burnout can result from a serious investment in one’s work (a desired goal for self-actualization), which transforms into chronic stress under the wrong conditions (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). With chronic stress, the resulting burnout can impair executive function, including difficulties to prioritize. Healthcare leaders must put physician wellbeing at the top of their agenda. They must promote the art and science of medicine for the benefit of the public health. Through concerted efforts to increase resilience and wellness during residency, training sites will produce physicians better equipped to manage stress and provide higher quality care to their patients. Online teaching modules helping to create wellness programs for physician trainees should start with understanding the importance of wellness, as well as with identifying methods to create a sustainable culture of resilience and wellness. There are steps physicians themselves can take to prevent the encumbrances of training and practice from depleting the joy out of medicine.

Definition of resilience and burnout. Resilience is our ability to bounce back from challenges or persevere despite disruption or chaos. Resilience is a foundation to wellness. On the other hand, wellness is a multifaceted concept that leads to optimal levels of emotional and social functioning. Wellness is more than the absence of illness. For physician trainees who have a variety of responsibilities and burdens bearing down on them, it is essential to be cognizant of the various elements that contribute to their overall wellbeing. Burnout is a psychological syndrome of overwhelming emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (i.e., feelings of detachment from the job), and decreased sense of accomplishment emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job (Maslach & Leiter, 2016). Burnout is described as “the index of dislocation between what people are and what they have to do” (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). In other words, it can be the outcome of an imbalance between various dimensions of work output (e.g., type of work, intensity, number of hours) and the opportunity to “recharge the batteries” (e.g., not enough attention paid to basic needs, including rest and reward).

Manifestations of burnout. The three main manifestations of burnout produced by chronic dislocation are: (i) a sense of exhaustion, (ii) cynicism, and (iii) professional ineffectiveness. These can have consequential problems with work satisfaction and professional performance, including patient safety (Tijdink et al, 2014). The research has shown an inverse correlation between the degree of emotional exhaustion and professional engagement (Tijdink et al, 2014). The willingness of physicians to work for the love of their job and not financial compensation or other form of recognition can, eventually, expose them to chronic stress and give rise to compassion fatigue. That is especially true in academic medicine, where there are less explicit limits on the academic and clinical balance of working hours. Many research studies have used the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) as a measure of burnout (Maslach et al, 1996). The MBI tool addresses three dimensions: (a) emotional exhaustion (i.e., feelings of being emotionally exhausted by one’s work); (b) depersonalization (i.e., an impersonal response toward recipients of instruction and care treatment); and (c) sense of lack of personal accomplishment (i.e., feelings of ineffective work achievement and competence) (Maslach et al, 1996).

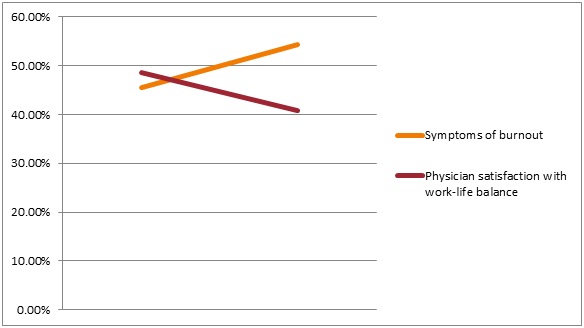

Prevalence of burnout. Much variability in the prevalence of burnout and its three dimensions has been found among physicians across the world. In a 2011-2012 U.S. national survey, medical students, residents/fellows, and early career physicians (five years or less since residency completion) were more likely to be burned out (all p < 0.0001) compared with the general population (Dyrbye et al, 2014). Burnout is prevalent in medical students (28-45%), residents (27-75%, depending on specialty), as well as specialist physicians (IsHak et al, 2009).

Because burnout in the medical community is an epidemic that starts early during the medical training and continues to manifest through the career practice years, addressing the physician burnout is the shared responsibility of both the individuals and the institutions in which they train and work. Given the strong association to patient safety, patient satisfaction, and quality of care, there certainly is an imperative for institutions to mitigate physician burnout and promote physician engagement. Although some factors driving burnout are greater than the institutions (see more details in section Integrate New Lifestyles), organizational-level efforts can, and should, have a profound effect on physician wellbeing. A concerted effort of the leadership starting from the highest level of the institution is the key to making meaningful progress.

Institutions need to develop an early active awareness of burnout and incorporate relevant interventions starting during the process of training medical students and resident physicians in order to foster increasing resilience of the medical community. Regarding physician burnout, which of the following statements is correct?

In a study of U.S. academic otolaryngologists (n = 351 respondents; 68% participation rate), 70% reported moderate to high burnout rates, but women experienced a significantly higher level of emotional exhaustion than men (Golub et al, 2008). In this study, high burnout rate was significantly associated with likelihood to leave academic medicine within the next one to two years (Golub et al, 2008). Similarly, a study conducted among U.S. emergency physicians (n = 1,272 respondents) showed that 60% had moderate to high burnout scores (Goldberg et al, 1996). Projected attrition rates in this study were 7.5% over five years and 25% over 10 years. A Dutch survey of medical professors (n = 437 respondents) at eight academic medical centres has shown that early career medical professors (younger age and fewer years since appointment) and having children living at home were factors significantly associated with higher scores of emotional exhaustion (Tijdink et al, 2014).

Academic women appear to face challenges and barriers to success in comparison to their male peers regarding their struggle to achieve academic advancement and to occupy the highest positions within institutions. This can lead to burnout symptoms and other serious consequences.

Given the fact that burnout is often a precursor to more serious psychological health problems, a meta-analysis has shown that the suicide rate ratio among female physicians is double compared with the general female population (2.2, 95% CI 1.9-2.7), and greater than their male peers (1.4, 95% CI 1.2-1.6) (Schernhammer & Colditz, 2004).

Publications. Despite the fact that the proportion of women in medicine is approaching that of men, female physicians remain in minority regarding reaching the highest academic positions (Jena et al, 2015). One reason for this disparity between the sexes may be that female physicians, in comparison to their male colleagues, have a lower rate of scientific publishing, which is an important factor affecting promotion in academic medicine (Fridner et al, 2015; Reed et al, 2011). Publication of scientific research is an academic currency for professional advancement, it determines status and prestige, as well as it serves to rank universities and professionals. Having a relatively low Hirsch index for publications was associated with higher scores of emotional exhaustion (Tijdink et al, 2014). A study has shown that 54% of medical professors considered that publication pressure was becoming “excessive” and was statistically associated with burnout (Tijdink et al, 2013). Physicians with more control over their work had a higher publishing rate (Fridner et al, 2015). Interestingly, work-related exhaustion was found to have a significant negative impact on the publishing rate among female physicians (odds ratio 0.2, 95% CI 0.1-0.7), but not in male physicians (Fridner et al, 2015).

Academic citizenship. “Academic citizenship” may be recognized through promotions criteria in the context of an increasingly performative academic culture, which can disadvantage women who publish less than their male counterparts (Macfarlane, 2007). How academic citizenship is rewarded, and how female professors “pay the price” for academic citizenship, are key elements to understand. Good academic citizenship requires an active engagement and participation in the life of the university, awareness of the institution’s strategic goals, and a willingness to integrate meaningfully the demands of the medical field with the needs and expectations of teaching roles and learners’ needs.

Remuneration. Studies suggest that academic women earn less on average than their male peers because they may focus on academic citizenship roles that can go unrewarded and not leading to promotion and, subsequently, pay rises (Macfarlane, 2007). In this vein, a recent study has shown that significant sex differences in salary exist among U.S. academic physicians even after accounting for age, experience, specialty, faculty rank, and measures of research productivity and clinical revenue (Jena et al, 2016). In a 2016 study analyzing sex differences in earnings among 10,241 academic physicians at 24 U.S. public medical schools, female physicians (n = 3,549 subjects) had lower mean unadjusted salaries than male physicians ($206,641 vs $257,957; absolute difference $51,315, 95% CI $46,330-$56,301) (Jena et al, 2016). A significant sex gap in salary remained even at the associate professor level when controlled for human capital, structural factors, and academic and clinical productivity (Claypool et al, 2017). Beyond remuneration, the moments of validation, and opportunities to prove our own self-worth to others and, more importantly, to ourselves, are essential factors to the pledge to mitigate burnout. Continuous efforts of academic institutions to metamorphose into non-gendered settings is a professional imperative.

Table 1 shows a summary of the consequences of untreated burnout in physicians. Further facts specifically on depression and suicide in physicians are presented below.

| Table 1. Key consequences of untreated burnout in physicians |

|---|

| Depressive disorder |

| Suicide |

| Substance use disorder |

| Interpersonal relationship problems |

| Physician turnover |

| Decreased quality of care |

| Increased medical errors |

| Decreased patient satisfaction |

| Decreased professional effort |

| Compromised role models for trainees |

The causes of suicide among physicians are the same as the general population; 70-90% of suicides are linked to psychiatric disorders. Depressive disorder is a major contributor to suicide, and other factors include bipolar disorder and substance use disorder. Suicide rates are higher among physicians who are divorced, widowed, or never married. Physicians who are at most risk for suicide are driven, competitive, and compulsive. Because of greater knowledge of lethality of drugs and easy access to means, the higher completion-to-attempt ratio for physicians contributes to the problem (Myers, 2017).

Although the predictive factors for burnout are further discussed in detail in subsequent topics of the section Know Yourself, we herein briefly review the interplay between occupational and individual factors. In order to prevent or mitigate burnout, one must understand its risk factors. The strongest predictors of burnout in the workforce have been inadequate research time, inadequate administration time, low self-efficacy, and dissatisfaction with balancing work and life (Golub et al, 2008). In a cross-sectional survey performed among U.S. emergency physicians between 1992 and 1995, the most highly ranked correlates with burnout were self-recognition of burnout, negative self-assessment of productivity, lack of job involvement, career dissatisfaction, sleep disturbances, increased number of shifts per month, dissatisfaction with specialty services, intent to leave the practice within 10 years, higher levels of alcohol consumption, and lower levels of exercise (Goldberg et al, 1996).

Although the predictive factors for burnout are further discussed in detail in subsequent topics of the section Know Yourself, we herein briefly review the interplay between occupational and individual factors. In order to prevent or mitigate burnout, one must understand its risk factors. The strongest predictors of burnout in the workforce have been inadequate research time, inadequate administration time, low self-efficacy, and dissatisfaction with balancing work and life (Golub et al, 2008). In a cross-sectional survey performed among U.S. emergency physicians between 1992 and 1995, the most highly ranked correlates with burnout were self-recognition of burnout, negative self-assessment of productivity, lack of job involvement, career dissatisfaction, sleep disturbances, increased number of shifts per month, dissatisfaction with specialty services, intent to leave the practice within 10 years, higher levels of alcohol consumption, and lower levels of exercise (Goldberg et al, 1996).

Workplace characteristics that have been found to cause burnout include an overloaded schedule, lack of control over workplace schedule, insufficient reward, absence of fairness, and conflicting values (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). For example, the health care system in the U.S.A. is fragmented, complex and the bureaucratic burden and administrative demands add pressure on the practicing physician. Electronic health records (EHRs) exacerbate the problem when the system is cumbersome and less user-friendly. In a recent pilot study conducted at a U.S. academic medical center, a strong positive correlation between the EHR use and resident physician burnout was found (Domaney et al, 2018). These authors suggested that time spent on EHR use may be an area of importance for medical educators to consider when seeking to minimize burnout and promote wellness. In a large U.S. national study, physicians’ satisfaction with their EHRs and computerized physician order entry was generally low (Shanafelt et al, 2016). Physicians who used EHRs and computerized physician order entry were less satisfied with the amount of time spent on clerical tasks and were at higher risk for burnout (Shanafelt et al, 2016).

In academic medicine, faculty burnout may be inevitable when the institutional culture promotes a model of medical professors as isolated businesspersons, encourages overwork, offers little recognition for good teaching and mentoring of trainees, and allows the faculty members to become “shock absorbers” for institutional stressors. In such environments, it is easy for misconceptions about burnout and depression, and the fear of stigma or consequences from admitting one’s mental health issues to delay help seeking, hence making the symptoms worse. Thus, it is not that some medical academicians just are not cut out for it. Institutions can, and may, cause burnout, and only a concerted effort of an institution can deal with it.

Furthermore, sexual harassment in the workplace certainly adds to the discrimination experiences and burnout. In a 2014 survey of U.S. clinician-researchers (n = 1,066 respondents; 62% response rate), 30% of women reported having experienced sexual harassment compared with 4% of men (Jagsi et al, 2016). Among women reporting harassment, 47% (95% CI 39%-56%) stated that they believed these experiences negatively affected their career advancement, whereas 59% (95% CI 50%-67%) perceived a negative effect on their confidence as professionals (Jagsi et al, 2016).

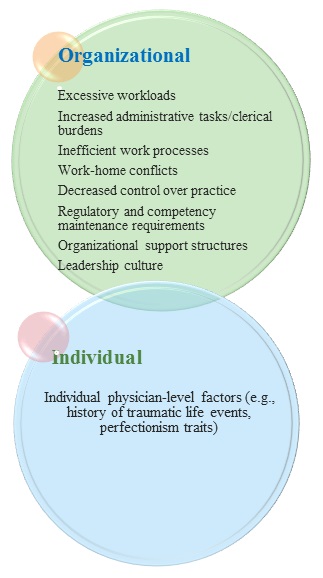

Figure 2. Contributors to physician burnout (Data derived from West et al, 2018)

Even in the current #MeToo era, reporting sexual harassment can be stressful; women who report sexual harassment may experience retaliation, stigmatization, and marginalization, which can lead to chronic stress and burnout (Jagsi, 2018).

Regarding individual risk factors, a cross-sectional twin study by Mather et al (2014) found that a history of traumatic life events (e.g., abuse, neglect) was associated with burnout. Early childhood trauma affects the stress response systems, which can become hyperactive and create a sense of overwhelm when facing stressors during adulthood. It is often true that people drawn to medicine tend to have traits that make them prone to potential problems (e.g., perfectionism, an exaggerated sense of responsibility, a compulsion for achievement, difficulty asking for help). For those choosing a helping profession like medicine, it is important to identify early on personal resilience factors. Figure 2 summarizes the contributors to burnout.

The rates of burnout symptoms that have been associated with adverse effects on patients, physician health, and healthcare workforce exceed 50% in studies of both physicians-in-training and practicing physicians (West et al, 2018). Factors of the physician burnout epidemic are largely embedded within healthcare institutions and systems, however, individual physician-level factors also play a role, with higher rates of burnout commonly reported in female and younger physicians (West et al, 2018) (see Figure 2).

"I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record."

- Gold et al, 2016

Stigma is prevalent among physicians. In a closed Facebook group survey of 2,106 U.S. female physicians who were also mothers, nearly 50% believed they met the criteria for a mental illness at some point in their careers but had not sought treatment due to stigma (Gold et al, 2016).

In this study, two-thirds reported that fear of stigma inhibited both treatment and disclosure (Gold et al, 2016). Moreover, one in three respondents said they received a formal mental health diagnosis since medical school. Despite this, only 6% of physicians with formal diagnosis or treatment of mental illness had disclosed to their state. These authors showed that stigma and licensing questions, particularly those asking about a diagnosis or treatment rather than functional impairment may contribute to treatment reluctance among suffering physicians (Gold et al, 2016).

Click below on all the perceived barriers to treatment in this case.

| Table 2. The 7 rules for physician resilience: R E S P I T E |

|---|

| REMAIN RESPONSIBLE: Be satisfied with the responsibility you take for your own wellbeing (physically, emotionally, spiritually, and financially) |

| EXPRESS EMOTIONS: Be satisfied with the way you express and manage your emotions (laughter, sadness, contentment, and anger) |

| STUDY: Be satisfied with your ability to study and be a student for your entire career |

| PRIORITIZE: Be satisfied that your life’s priorities are yours and clearly reflect your values |

| INFLUENCE: Be satisfied with your ability to have a positive influence at work and in life |

| TRANSFORM: Be satisfied with your commitment to initiate and embrace change and transformation at work and in life |

| ENCOURAGE: Be satisfied with the way you ask for and receive assistance and encouragement from others (professionally and personally), when in trouble |

Self-awareness and the knowledge of one’s own limits is the foundation to a healthy life balance. Professionals should know themselves so that precursor symptoms of exhaustion become clearly identifiable signals that allow prompt adjustment of the workload and coping skills. For example, growing up with an alcoholic parent might make the child unaware of his/her own needs (because of parental neglect) and, as an adult, he/she might continue to put other people’s needs first and ignore signs of exhaustion. Sometimes, a psychotherapeutic process is necessary for the professional to learn more about how the past has affected his/her specific coping under stress, and how to optimize resilience factors to prevent burnout recurrence. Making sure one continues to find meaning in one’s job helps giving a sense of reward and enhancing self-efficacy.

But such individual measures are insufficient without supportive infrastructures and organizations. Institutions must meet the goal of gender equality, with adequate career planning and talent spotting as part of an overall strategy. At an institutional level, modification of risk factors for burnout such as allowing sufficient faculty time for research and administrative activities may prevent or reduce the development of burnout and its deleterious consequences. Setting a series of clear “academic citizenship” expectations should be the goal. An attitude shift should also occur to destigmatize the sufferer (who can often be blamed or perceived as weak, while in fact the issue can be systemic and multi-layered).

Moreover, training gaps in nonclinical skills are still prevalent, with resulting symptoms of burnout and anticipated substantial attrition of physician numbers in the future (Gorelick et al, 2016). Changes in graduate medical education and healthcare delivery are greatly needed and should have important consequences for the workforce in healthcare system. Educating medical trainees early on and allowing for group supports to take place can help decrease isolation and increase empowerment when individuals combine their effort and ideas to create an impact by catalyzing organization change.

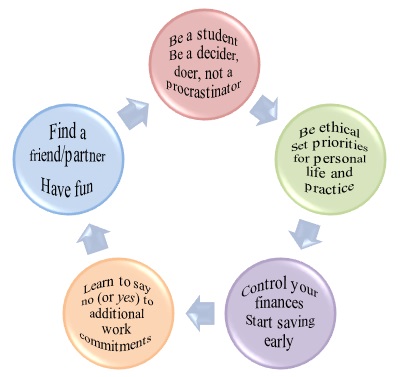

A balance between personal and professional lives is essential in order to prevent burnout. Figure 3 illustrates an example of physician self-care toolkit. Physicians often have trouble with finding a balance. They take work home, often do not “switch off” once at home, and often do not take the time to “recharge their batteries.” They should be given permission and encouraged to practice what they preach and make room for mindfulness practices. A life lived as mindfully as possible means being aware of one’s own experience as one experiences it (whether it is an emotion, a thought, a body sensation, or a situation). It increases feelings of wellbeing and decreases distress. Dispositional mindfulness has been shown to have a buffering effect against perceived stress and burnout; it is a resiliency factor and it can be taught (Lebares et al, 2017).

Physicians are never done learning and should expect to always find time to be a student for their entire career, but if they learn or study “mindfully”, one concept at a time, they will be more focused and effective, and generally more satisfied because they will be ruminating less about past mistakes or not worrying so much about the future. Developing a personalized toolkit with activities having a “high mindfulness index” for a specific individual (e.g., colouring, gardening, jogging) could be a strategy developed during a workshop or faculty development seminar.

Figure 3. Essentials for physician self-care toolkit

Physicians are expected to be ethical, use good clinical judgment and do what is right and in the best interest of their patients. Being a disciplined decider and doer prevents from becoming a procrastinator and can bring balance to the busy professional. Collaboration and collegiality should be high on everyone’s list. Balint groups, narrative/reflection and interest groups, or specific associations can be created to allow the sharing of resources. Peer conversations centred on the experience of doctoring were found to be beneficial by some physicians (Beckman et al, 2012), and they can start during the training years during Healer’s Art course, for instance.

Good relationships are strengthened when we all do our share of the extra-instructional work. Interdisciplinary collaboration to enrich the educational experience and mostly for the opportunity to collaborate with colleagues is essential and can enhance a sense of agency through the latitude and freedom experienced from pursuing specific interests. Encouraging civil and gracious behaviour in every setting should be on everyone’s minds; kindness breeds kindness. Reports favouring a reflective approach to the year’s work should be considered.

Undertaking new responsibilities should prompt physicians to ask themselves: “Will this commitment enhance my career at the expense of taking away from my time with family/friends, or lead to balance or imbalance in my life?” Setting priorities for personal life and academic and clinical practice is essential. It is important to not lose perspective and stay connected with core values rooted in an authentic sense of self. A quick road to burnout is ensured by taking on too many projects and responsibilities. Henceforth, learning to say no (or yes) to additional work responsibilities is vital.

Although many medical trainees have debt by the time they graduate, they must learn to control their finances from early on. However, physicians should not confuse their net-worth with self-worth. As individuals, social connection is paramount. Finding a lifetime partner or friend is a needed ingredient for wellbeing. Lastly, physicians always take their clinical and academic practice earnestly, but they should also learn to have fun by injecting a dose of humour into their daily activities. Humour is one of our most valuable resources in the efforts to control stress.

Table 3 presents a summary of principles and strategies to promote physician wellness (Kuhn & Flanagan, 2017). Moreover, Thomas et al (2018) have prepared the Charter on Physician Wellbeing and highlight that governing bodies, policy makers, medical organizations, and individual physicians all share a responsibility to proactively support meaningful engagement, vitality, and fulfillment in medicine. They set forth guiding principles and key commitments as a framework for key groups to address physician wellbeing from medical training through an entire career (see Table 4) (Thomas et al, 2018).

| Individual/professional level | Administrative level | Institutional level | National (policy) level |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Self-care:

Lifestyle hygiene (e.g., sleep, diet, exercise, mindfulness, mind-body practices, socialization) Discussion groups Shared stories Peer support and advocacy to challenge stigma Expanding interests/cultivating hobbies Developing a toolkit Utilizing psychotherapy, cognitive restructuring (e.g., “excellence is not perfection”, “be the best you can be” rather than "the best") |

Flexible schedules

Less cumbersome electronic health records and billing requirements Adjusting clinical productivity expectations |

Leaders should emulate desired wellness behaviour

Increasing employee satisfaction Professional development Screening tools for distress Education to address misconceptions/prejudices Sensitizing medical trainees early on during their studies Mentoring support Adjusting academic productivity expectations |

Educating the public to address barriers to access care

Easing credentialing barriers (focus on functional impairment rather than diagnosis) Funding research to identify risk and resiliency factors of work-related burnout |

| Guiding principles | Key commitments |

|---|---|

| Effective patient care promotes and requires physician wellbeing | Societal commitments: to foster a trustworthy and supportive culture in medicine; to advocate for policies that enhance wellbeing |

| Physician wellbeing is related to the wellbeing of all members of the health care team | Organizational commitments: to build supportive systems; to develop engaged leadership; to optimize highly functioning interprofessional teams; to appreciate that physician wellbeing is a shared responsibility |

| Physician wellbeing is a quality marker | Interpersonal and individual commitments: to anticipate and respond to inherent emotional challenges of physician's work; to prioritize mental health care; to practice and promote self-care |